The Evolution of the Juvenile Justice System: Insights from Dr. Mary Livers

Today, we sit down with Dr. Mary Livers, a leading expert in juvenile justice with a career spanning nearly 45 years. Mary has dedicated much of her work to transforming the way we treat young people in the justice system.

As a former Deputy Secretary of the Louisiana Office of Juvenile Justice and the founder of Livers Corrections Consulting, Dr. Livers has seen firsthand how the juvenile justice system has evolved. In this interview, she shares her insights on the history, current state, and future of juvenile justice, offering valuable perspectives for professionals working in juvenile justice facilities, as well as those involved in policy and leadership.

Read on to learn about the history of the juvenile justice system, how we got where we are today, and what Mary hopes to see coming down the road.

Can you share with us the historical context of the juvenile justice system?

Mary Livers: As early as colonial times, people were dealing with kids who were not conforming to rules and regulations of the day. Some kids were treated like adults in the court system, even as young as seven years old, which is mind-blowing. The thinking at the time was that kids possessed the same capacity for intent and understood responsibility (which, of course, we know now is very much not the case).

When the 19th century came along, reformers started looking at this whole issue of kids and childhood. The cities were growing, and there was industrialization and urbanization, which led to concerns about delinquency. In response, some reformers came around in 1825 or so and started providing guidance regarding education and trying to turn kids into compliant children. In the early 1900s, the first juvenile court was put into action in Cook County, Illinois, and it was founded on the principal of parens patriae, which means that the state steps in and takes over for the raising of the child in place of the parents.

That’s when you started seeing more and more youth being separated from their families and being addressed through informal hearings and the court system.

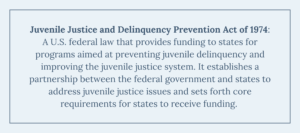

Throughout the 20th century, we’ve undergone probably the most significant evolution of how we treat juveniles. In 1967, a landmark Supreme Court case In re Gault established the right for counsel, notice of charges, right to call witnesses and the right of due process for juveniles. The official beginning of extended reforms was in 1974 with the JJDPA, the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act. This federal initiative began addressing deinstitutionalizing juvenile settings. Those youth who were considered “status offenders,” which are kids being charged with an offense that, but for the fact that they’re children, would not be a criminal offense – such as skipping school or violating curfews – were no longer to be held in juvenile detention.

As social science research started to proliferate, more distinctions began to evolve between the youth having behavioral issues versus kids who were in fact committing adult-type criminal offenses. In recent decades, there’s been a lot of progress around more informed strategies to address youth in our systems. The brain science contributed to the field in understanding the nuances of dealing with youth versus adults. We now know that the part of the human brain that regulates emotion and decision making is not fully developed until the age of 25. That explains adolescents’ sometimes erratic and impulsive behavior.

In addition, there is now well-developed science around the most effective approaches to improving decision making and prosocial development based on individualized needs and risks. As these interventions are put in place with appropriate adult staff role models and fidelity, we are seeing much more successful outcomes.

What were the original objectives of the juvenile justice system and how have those objectives evolved over the years?

Mary Livers: Even since the early reformers of the 1800’s, the intent has always been to turn kids’ lives around—to help youth get a chance at having a good life.

A lot of good research has pointed us to the whole idea that every child is an individual, and they all have their own paths. They all have individual needs and risks. Where we are today is we look at every child as a person who has a background, perhaps with trauma issues; and some are not a risk to the public safety. Most of the kids probably can be better treated in the community versus separating a child from their family and placing them into an incarcerated setting. It’s a completely different approach from where we were, say even 20 years ago.

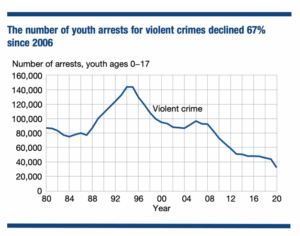

Why are fewer youth incarcerated today compared to previous years?

Mary Livers: Systems have started to embrace the research and are designing their systems to be responsive to what the science says will have the most positive impact on changing a youth’s trajectory away from the justice system. Youth that are low risk for re-offending or low risk for violence are receiving needed services based on their individual needs, at home in their own communities. The youth that pose the greatest risk—for either future chronic delinquency or a high risk for violence—are the youth being housed and treated in secure care. Theoretically, only youth who are deemed a threat to public safety are placed in the highest level of secure care. This has resulted in the numbers of youth in secure care to drastically be reduced.

How does the composition of youth in today’s facilities differ from that of the past?

Mary Livers: Historically, there were many kids in secure care who were low risk. Placing low risk youth in a secure environment was quite possibly increasing their risks, instead of decreasing risks. Given that, when low risk youth were no longer sent to secure care, the population at secure care became an increasingly more challenging group of young people. That’s where we are today.

You mentioned the higher concentration of high-risk youth now in today’s secure facilities. What are some of the consequences of this scenario?

Mary Livers: We obviously have youth who have a lot of challenges, many with complex issues. They may have a combination of mental health problems. They may have substance abuse problems. They may have oppositional defiance issues. You get kids that are coming into the system that are high risk, that have a lot of environmental factors with very nuanced interactional complexity. Some of these youth may also be affected by poverty and unstable home environments. These youth have experienced and seen trauma, more than anybody can imagine. Sometimes there’s a lot of anger that develops and can impede progress. Anger comes out in aggressive behavior and those are all very difficult to deal with. It makes for a very challenging situation.

How is the juvenile justice system adapting to address the increasing mental health challenges of youth entering the system?

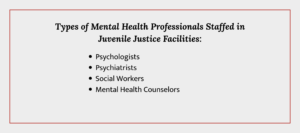

Mary Livers: Systems are recognizing the high percentage of youth that are incarcerated that have serious mental illness. As a result of that, systems are addressing that by improving the mental health services that they offer – making sure we have a robust group of staff that are credentialed professionals with the appropriate accreditations to serve this youth, such as psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and mental health counselors. Many systems have been very successful in bringing that part of the workforce in to assist with these really complicated problems that youth have.

How does this affect staff and facility operations? What challenges are posed due to the change in the concentration of high-risk youth in these facilities?

Mary Livers: Part of the issue is that some of these youth that reside in these secure care facilities are truly children – mentally they haven’t developed impulse control. Some of them don’t have a moral foundation of “right” and “wrong.” Youth can learn it, but they often come in with these kinds of challenges.

There are also physical challenges. Some youth are physically intimidating – they look like they’re 19, 20 years old (some youth might even be 19, 20 years old in some of these incarcerated settings). It can be rather daunting for staff to set boundaries with youth that are impulsive, that have a strong overbearing physical appearance. Quite frankly, some people cannot work effectively in that environment. Some people are just too fearful, and they may feel threatened and not safe. Of course, a person with these feelings should not work in the direct care of youth in this environment.

“It takes a special kind of person who can feel confident in working with youth in this population. It takes a certain kind of person that has the ability to set boundaries and gain the respect of youth.” – Mary Livers

It’s really a very special person who wants to work with youth and who is not easily intimidated by physically large youth that are acting out in some way. It’s really hard to get a stable workforce established in some of these facilities. Particularly in our current time, when having a stable workforce is almost hard in every industry. We find it very difficult to recruit the right people and provide the appropriate training so that the staff feel confident in dealing with the youth; not to mention being able to actually retain people. A lot of people who want to do this work find out that it’s hard. You’re working with teenagers and the teenage years are the most difficult. It’s hard to find people who have the heart and the passion and the commitment to stick with this work, especially over time. This work can be both heartwarming and heartbreaking at the same time.

How does facility design impact the situation? How can it aid in the success of juvenile rehabilitation?

Seen above: examples of spaces in US juvenile facilities that employ best practices for normative design, including bright colors, abundance of light, familiar textures, and an overall campus-style feel.

Mary Livers: Design has a tremendous impact – especially for those dealing with mental health challenges. We all want to be in a nice environment. We all want to be in an environment that is welcoming and is not punitive. When systems have a chance to design a physical plant that is reflective of the philosophy of good programming for youth, then it’s a great opportunity to be able to align your physical surroundings with the philosophy that you’re trying to operate out of.

Designing facilities that are welcoming, have a lot of natural light, feel open, feel non-restrictive… that’s going to communicate the kind of normative things that we want to bring to the environment. It’s great if we have facilities that are less punitive looking. It feels more like a campus. It’s about creating a positive environment as opposed to everything around you looking like a prison. That is only going to reinforce a negative perception of yourself.

Some areas are moving toward harsher punishment for juvenile residents. What are your thoughts on this shift?

Mary Livers: I would hope that our policymakers will continue to rely on research that tells us what’s most effective. Everything that I know about the research about children is that just giving them harsher punishment is not the answer. In most states, there’s something in place that addresses the most serious violent crimes committed by a juvenile. There are already sensible paths for the district attorney to make a case that this kid should be put in the adult system – they have to prove that they are beyond rehabilitation as a juvenile. If they can make that case – and I would hope that the bar would be high on that for the judge to say that somebody cannot be rehabilitated – they’re going to have to spend 20 or 25 years in the adult prison.

There may be a handful of cases that should be considered in this way, but those cases should be rare. After all, that is what the juvenile system is supposed to do: take juveniles, serious offenders, and give those kids what they need – an effective intervention so that they don’t commit any more serious acts that endanger public safety. I’m against just doing more punishment because it looks good or the public is calling for it. I hope we have statesmen and women in the legislatures that will not take the bait and advocate for harsher punishment just because it “feels good” in the public discourse.

I’m not saying that youth should not be punished. There has to be consequences. Secure care is a needed level of care in our systems. I am convinced that if we don’t have this level of care, more kids will end up going straight into adult systems, which nobody thinks is a good idea, including most wardens I know that run adult prisons.

There’s only so much punishment you can give somebody. This is what needs to be emphasized: punishment alone does not change behavior. Punishment is a consequence, but beyond that, we have to provide something in addition to the consequence to effect change. Do kids need consequences? Yes. If you think about kids, they learn pretty quickly. If the consequences are swift and consistent…if they’re not overly harsh and they’re replaced with something more positive… that’s the formula for change in behavior. We’ve been very heavy-handed in our history with punitive measures, and I don’t think it’s given us the results of changing behavior like we would like for it to.

Give us your thoughts on tools like restraint chairs and tasers. How do tools like these impact the management of youth and facilities?

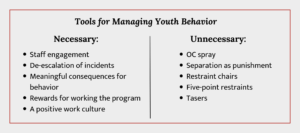

Mary Livers: I’m going to make a bold statement here, and that is: if the facility is truly run with a treatment modality of structure and has the right complement of staff, you don’t need to have restraint chairs, tasers, or other adult type use of force tools.

If you are fully staffed and have implemented a well-structured, safe program, it would be rare that you would ever have to use any type of law enforcement restraints with youth. The most effective way to provide a safe and secure operation is to use the positive tools you have: staff engagement, de-escalation of incidents, meaningful consequences for behavior, rewards for working the program and for lowering their risk levels, and a positive work culture.

Staffing and safety are big issues, however, and are correlated. If you don’t have adequately trained staff allotment, then I recommend that these items be on hand in a controlled setting, only to be accessed by permissioned high-level staff when a situation is deemed out of control and a threat to the safety of staff and youth. Again, if you’re staffed adequately and you have a robust treatment program that has fidelity, you really don’t need to have all those external uses of force equipment available.

What role does rehabilitative justice play in reducing recidivism among juvenile residents?

Mary Livers: In juvenile justice, youth have a right to treatment. In fact, the Supreme Court has said if you are going to separate children – those 18 years and younger in most states – from their homes, their schools, so forth, you have to provide treatment. You can’t just punish the kids by taking them away and putting them in some place. You have to do something that’s rehabilitative. That’s the whole objective of juvenile justice. The whole mission is rehabilitation – to change criminal thinking, change criminal behavior.

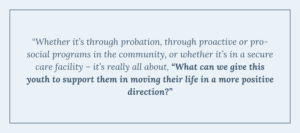

There’s so much more that can be done to help change criminal behavior than just punishment. For instance, the whole positive youth development movement is about not trying to catch kids doing something wrong, but to catch kids doing something right and build them up – it’s strength-based. It’s saying, “What is this individual’s strength?” and building that person up on their strengths and helping them to see where they can improve, not focusing on negative stuff all the time. Some of these youth have never heard anything or experienced anything hopeful in their young lives, so bringing youth in where there’s a community program – whether it’s through probation, through proactive or pro-social programs in the community, or whether it’s in a secure care facility – it’s really all about, “What can we give this youth to support them in moving their life in a more positive direction?” It’s about common sense and the power of positivity in addition to consequences for negative behavior.

In addition, one aspect of treatment that I don’t think gets enough attention in our conversations is about restorative justice. This methodology is a very good tool to help develop a moral sense of right and wrong, the effects of our actions on others, and to help develop empathy for all human beings. We should use this methodology in as many ways as we can in our interactions with youth.

What changes would you prioritize to ensure that youth receive the most effective treatment and rehabilitation possible?

Mary Livers: I wish there was a way that legislative reform could only go into effect if it had some type of science behind it. I just see so much going back and forth on policy. It seems every four years, there’s a shift in philosophy on punishment versus rehabilitation. In recent years, we had a spike in juvenile crime in Louisiana, so they reverted the age of majority from 18 back to 17. When a youth turns 17, they can be charged as an adult. It seems that our policies just go back and forth based on the reaction to certain events that occur. I wish there was a better way for discussions to take place around this important topic rather than just what “feels” right to people.

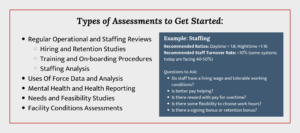

For jurisdictions and agencies looking to improve their juvenile justice systems and facilities, what are the first steps they should take in addressing the current issues and implementing more effective solutions? Where do they really start the process?

Mary Livers: I think having an outside entity that is well versed in this very unique field come in and assess all aspects of the operations–looking at policies and comparing them to operational and best practices–would be a great idea. It is always good to have extra eyes and ideas to consider effectiveness of programs. Having an assessment of operations to see if they’re conforming to best practices, promising standards of operation, and best practices around staffing issues would be helpful. That’s always a healthy first step for people to look at.