Revealing the Hidden Costs in Higher Education Facility Maintenance

Maintaining the physical infrastructure of higher education facilities is a complex task that involves a variety of factors. When equipment malfunctions or systems fail, corrective maintenance steps in to address the issues and restore functionality. During my six years leading and overseeing maintenance of higher education facilities, as well as my 17 years of experience in overall facility maintenance, I’ve witnessed firsthand the importance of recognizing hidden expenses and their impact on systems and budgets.

Where’s the Money Coming From? A Budget Balancing Act

Corrective maintenance ripples through an institution, touching multiple departments and budgets. Depending on the nature of the problem, different departments may be affected. When a critical component fails, such as boilers, air handlers, fire pumps, chillers etc., the immediate question arises: “Where’s the money coming from?” The reality is, the financial burden of corrective maintenance doesn’t just fall on one department; it’s a balancing act that requires strategic resource allocation. Higher education institutions must consider their overall financial health and priorities to determine how to distribute the cost impact. This might involve reallocating funds, adjusting budgets, or seeking additional funding sources.

While the immediate repair cost is evident, the true cost of corrective maintenance goes beyond the surface. In this blog post, we delve into the multifaceted nature of corrective maintenance expenses and share six key considerations to shed light on the hidden costs that educational institutions often face:

1. Your number one investment should be a solid preventive maintenance plan

One way to manage the true cost of corrective maintenance is by investing in preventive maintenance strategies. Regular inspections, maintenance, and predictive technologies can identify potential issues before they escalate into full-blown failures. For example, replacing filters on an air handler provides routine inspection and prevents build up on the face of the coil that could result in catastrophic failure. Routinely pulling strainers and flushing coils will help keep hydronic systems operating properly. This would prevent pump failures, coil failures and rupturing of coils that would impact more than just HVAC systems. While preventive maintenance incurs its own costs, it often proves to be more cost-effective in the long run by reducing the frequency and severity of corrective maintenance expenses.

2. Redundant critical systems must be properly maintained

Corrective maintenance begins with identifying and repairing faulty equipment before absolute failure. The immediate cost encompasses not only the price of replacement parts but also the skilled labor required for repair. These type of costs may seem like a no-brainer but what happens if you don’t have a redundant system in place and working properly while you’re repairing the faulty equipment in question? That’s where the unforeseen costs can really start to add up.

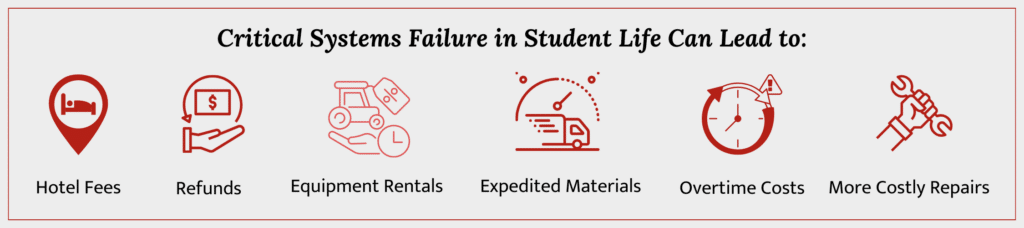

Choosing not to have and maintain redundant systems in a timely manner will increase costs exponentially. The expedited material and overtime labor at the time of a catastrophic failure is one cost. In addition, often times this is coupled with equipment rentals to maintain critical systems in the building. When critical systems fail in student life, universities most often have accommodation costs for residents to stay in hotels or refunds, too.

Identifying redundant systems and maintaining their integrity, meaning keeping them maintained and part of your ongoing preventative maintenance schedule, is imperative to the facility’s infrastructure. Although the upfront cost to replace or add redundant critical equipment, such as a chilled water pump, may be easy to calculate, the real, hidden costs of not addressing this need immediately can go far beyond the cost of initial replacement or addition.

3. Don’t forget about additional services and setup costs

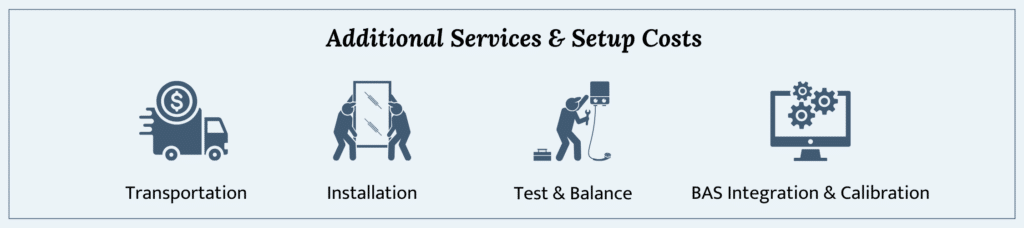

Beyond the equipment itself, there are often supplementary services and setup costs to consider. For instance, when replacing a piece of equipment, such as supply fan motors, energy wheels or booster pumps, there might be associated expenses like transportation, installation, test and balance, BAS integration and calibration. These secondary costs, although not immediately apparent, contribute significantly to the overall expense.

4. Monitor BAS data at the campus level and for individual facilities

Utilizing building automation systems (BAS) to monitor major building equipment is crucial to operations and facility management. Having a reliable BAS to diagnose, monitor, and run analytics can improve system maintenance and response. A reliable BAS with the necessary data can mitigate costs for unnecessary repairs and time to diagnose system issues.

Oftentimes, facilities have obsolete controls systems. Specifically in the university system, energy utilization is not being monitored for each structure. It is often monitored from the central plant, which makes identifying sustainability issues difficult. Recording system data for each structure can allow us to identify problem areas and lower the cost of utilities.

5. Before you repair or replace, check for underlying causes

Incorrect prioritization of projects is another key component to increased long-term maintenance costs. A common theme in university housing is to repair or replace what is evident from a visual perspective, painting, carpet, ceiling tile etc. Although these items do need to be addressed, there are often underlying problems that are not seen causing these replacements.

Cracked paint showing up throughout the interior? There could be humidity issues in the building that need to be prioritized before painting. Stained ceiling tiles or moldy carpet? There might be leaks in the plumbing or hydronic piping throughout the structure that are at the root of the damage. By putting the paint brush down and taking a step back, we can address the underlying issues first, and thereby mitigate the continuing cost of maintaining the visual/interior components of the structure.

6. Understand the original design intent before proceeding with new equipment or components

Design flaws often occur when additional equipment or components are added to the structure without the review of the original design or capacity of those systems. For example, a design flaw could be that the hydronic piping is improperly sized or includes too many 90-degree-angles, resulting in additional pressure drop causing a pump to cavitate. This would impact the efficiency of the pump resulting in higher lifecycle costs.

That’s why it’s important to always consider the original design intent when upgrading or replacing equipment and systems. Collaborating with designers and engineers will help determine the best solution at your disposal; and any fees associated will be offset in the longterm through improved equipment efficiency and longterm energy cost savings.

Conclusion

The true cost of corrective maintenance in higher education facilities extends far beyond the immediate repair bill for replacement parts and service. From the equipment itself to additional services, setup, and the impact on various departments’ budgets, it’s a multidimensional financial challenge. By understanding these hidden costs and investing in strategies like preventive maintenance, critical system redundancy, and BAS optimization, institutions can make more informed decisions, ensure efficient resource allocation, and create a more sustainable and well-maintained campus environment for both students and staff.