The Jail of the Future: A Vision of 2030

Over the span of my career designing jails and detention facilities, I have seen a radical evolution in the philosophy of jail operations and design unthinkable 40 years ago. One of the first jails I designed had steel bars on the cell doors and the windows, because the sheriff at that time insisted on these features. Even after traveling to California to see the latest in “new generation” jail design, he was unimpressed and still insisted on steel bars… then a new sheriff was elected just before the opening of the new facility. As the new sheriff toured the new jail, he became upset. “Who,” he demanded, “was the architect that designed such an outdated building?”

Since that time, novel ideas in jail design have come to be an accepted practice: direct supervision, security glazing in lieu of steel bars, courtrooms in the jail, open intake waiting areas, contact visitation, and so forth. Today, we are on the threshold of another massive change in the way we think about jails.

Today’s Jails

In today’s society, jails are asked to do too much. They are asked to address the failure of the justice system, the incarceration and care of the mentally ill, the need for education, and the problems of civil society as well—all of which create a stream of young, disturbed, addicted, and disabled citizens flowing into obsolete, unsafe, and unhealthy jails. In addition, jails are blamed for being over crowded, punitive, unsafe, and unhealthy.

Although there may be a truth to these accusations, it is through no fault of the jail administrator. Physical plants are old with outmoded design layouts, and elected officials refuse to provide funding for basic repairs. Detention staffs are trained to provide custody and control, but the current jail populations require professionals who are trained in clinical diagnosis and treatment modalities.

In addition, inmates are cutoff from their family, friends, and neighbors during their incarceration. Perhaps the most troubling aspect of their time in jail is its hiddenness. Sunlight is the best disinfectant in a democracy, both literally and figuratively. The average citizen does not see and appreciate the deadening effect of idleness, monotony, and isolation—and the danger that other inmates pose for the unsuspecting detainee. Elected officials have no reason to spend political capital on expensive jail upgrades. Unlike schools or hospitals, there is no voter constituency clamoring for the reform of our jails. Unfortunately, it often takes a suicide, deaths in a fire, or a similar tragedy to stir the conscience of elected officials and shame them into improvements.

Some jails routinely invite community volunteers into the local jail to provide counseling, reentry connections, and other pro bono services. The presence of volunteers is a good barometer of the control level exercised by the jail’s administration and goes along with a sense of pride. For example, when I enter a jail for the first time, I immediately look for cleanliness. Is the lobby clean? Do the floors sparkle? Are there wrappers and debris lining the baseboard of the corridors? Cleanliness and tidiness tell me that someone cares about their surroundings, which in turn sends an unspoken signal that there are rules for expected behavior.

A Call for Community Participation

In his book The Machinery of Criminal Justice, Stephanos Bibas (2012) argues that the criminal justice system as we know it has lost its way, and in doing so, has lost its legitimacy. The larger community sees the justice system—especially courts, prosecutors and jails—as isolated from their values, in addition to being self-serving and impersonal. Bibas also argues for more personal involvement, more personal responsibility, and more opportunities for the “community” to participate, and in their way to restore the legitimate role of the justice system.

Our decentralized system of government has bred more experimentation at lower levels: community policing, problem-solving courts, restorative justice, medical marijuana decriminalization, and faith-based programs that began as local experiments and were copied elsewhere. Tight budgets also encourage experimenting with less expensive alternatives to long-term incarceration.

Seven empirical studies reviewed by Bibas (2012) found restorative justice performed better than traditional criminal justice on all dimensions studied: victims and wrongdoers were more likely to think that the system, their judges or mediators, and the outcomes were fair. It is time for legalese, procedural technicalities, and unfettered back-room deals to give way to more transparent and participatory procedures.

The government’s monopoly on criminal justice blinds it to the valuable human interests and needs of the larger community of family, friends, neighbors and victims. Crimes harm real people, who deserve more consideration and power in criminal procedure. Mediation and other face-to-face interactions between victims and wrongdoers offer this hope. Let’s peer into the future and try to imagine the unthinkable.

Welcome to the Year 2030

The future success of our society is as much tied to the fate of those left in the wake of progress as those on its leading edge. Facilities designed for the incarcerated need to be planned and designed with outcomes in mind every bit as much as an academy for prep school students. Obviously materials and treatments will differ, but this same care for scale, humane materials, healthy environment, and all of the metrics of energy efficiency should apply equally.

Time spent incarcerated is time stolen from one’s potential. In 2030, elected officials who are committed to sustainable justice always begin the jail planning process with the question: “How small—rather than how large—should we build our new jail?”

Good Neighbors

In the year 2030, the jail is located downtown next to the courthouse, allowing for easy movement of inmates and reducing the number of vehicle trips required from a remote jail. It is accessible to public transportation, which meets a sustainable design goal and provides humane consideration to maintain the human connection for families, friends, and attorneys.

Downtown buildings have a smaller footprint than a one-story out-of-town building. They conserve land and have much less roof area, thereby reducing the heat island effect and the amount of storm water run-off to be stored, treated, and discharged. A smaller building means a reduction in site disturbance, materials, domestic water usage, energy, and staffing.

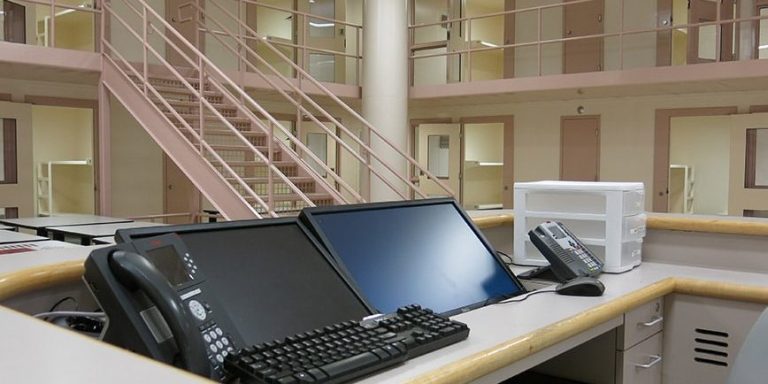

Jail Design

The jail of the future is oriented in an east/west direction to capture sunlight during winter and to guard against heat gain in the summer. The building itself is narrow and wrapped around an outdoor courtyard in the shape of a square doughnut. The exterior envelope of the building forms the secure perimeter. Exterior materials can be masonry, brick, pre-cast stone, or glass. Because this is a sealed building, the outside can be designed with various expressions, so that it can look like a library, a community college, or a museum. The courtyard created inside the square doughnut provides a daylight-filled corridor along all four sides, which in turn reduces the energy consumption for artificial lighting in a building that operates all day, all night, every day of the year. Bringing daylight into the correctional environment reduces stress for inmates, reduces absenteeism and sick calls for staff, and lifts the spirits of all.

Daylight and views from the dayrooms (including vibrant colors, excellent sightlines, climate control and acoustic dampening) create a positive staff attitude and promote an environment conducive to positive behavioral change in inmates, and hopefully a more successful outcome—reinforcing the interrelationship between the three scales of sustainable design: the environment for individuals using the spaces within; the building itself; and the community.

A Better Environment

Green justice buildings require a green justice system that supports and contributes to sustainable communities. For the buildings that form the justice system—courthouses, detention centers, and law enforcement facilities—this linkage is manifested in a mission statement that goes beyond a traditional reactive response to a problem-solving approach that seeks to improve the communities they serve.

We know that environment cues behavior. Research over the years demonstrates that inmates respond better in a normative environment than in a traditional cellblock. Normative environments contain natural light, sunlight entering and hitting the floor, views to the outside, vibrant colors, natural (or at least normal) materials, acoustic dampening, personal space and control of some personal territory, good sightlines along with the roundthe- clock presence of a correctional officer to maintain order. Normative design features support the sustainable goal of humane and dignified environment.

A Growing Link to the Future

As the acceptance of shared responsibility for the environmental health of our planet becomes widespread, a growing link develops between sustainable design, social justice, and economic development. This triple bottom line is the full measure of the effectiveness of the justice systems that serve our communities. (AIA Academy of Architecture for Justice, 2010).

Sustainable justice facilities offer the community a broader and more user-friendly set of options for when, where, and how to access the justice system. The contributions to sustainability occur on three scales in three areas.

- Scale of Community—The purpose of the justice system is to protect public safety by channeling deviant behavior into acceptable norms so that all citizens can have meaningful roles in their communities. Various scholars have proposed innovative alternatives to plea bargaining including the creation of “plea juries,” that is, lay panels that would inject community values and check excessive leniency or harshness in plea bargaining (Bibas, 2012). We can no longer afford to give every victim and defendant a full-blown jury trial. But there ought to be ways to hold much shorter jury proceedings, free of technicalities. Victims and wrongdoers, their families and friends ought to see justice done by doing justice themselves. The dishonest forms of plea bargaining, fact bargaining, and charge bargaining must end. In this way plea bargains would begin local conversations. Insiders would no longer dictate outcomes to outsiders, (i.e., the larger community of family, friends, neighbors and victims).

- Scale of Building—Larger counties are stuck in a conceptual quagmire. These big, bureaucratic governments only know how to mobilize large scale solutions. Lacking suitable sites (due to NIMBY [“not in my backyard”], environmental reviews, etc.) they are tempted to resort to highrise buildings or to sites away from center city. Both solutions are conceptually deficient and operationally obsolete at the outset, and can only make the “problems” worse. What’s needed is a re-definition of the “problem.” It’s misguided to start with the solution (“What should our new jail be?”). Instead let’s re-state the problem: How do we deal with chemical dependencies, mental health issues, homelessness, and extreme health issues? All these issues present themselves, sooner or later, in a crisis on the street. Building a new jail is not the answer to these challenges. More creative approaches are in the works.

- Scale of Individual Experience— The physical needs, health, dignity, and human potential of all who come in contact with the justice system are respected and given the opportunity to flourish. This applies equally to staff, visitors, service providers, and detainees. Research suggests that the public wants not more punishment, but more accountability (Bibas, 2012). The antidote for antisocial crimes is enforced pro-social behavior and responsibility: quit drug habits, learn a skill, get a job, be reliable, support your family, and pay your debts to your victims.

The “Three-Door” Jail

In the year 2030, smaller counties are moving toward a “three-door” jail model. In this model a person picked up on the street would be go through one of three “doors” designated as:

- Detention—the classic secure jail setting.

- Diversion—the classic movement into release on recognizance or third-party release.

- Deflection—movement into a “stabilization” center or a “sobering” center. Because most States no longer allow involuntary admission to a mental facility (except in extraordinary circumstances), the stabilization modality requires skilled crisis intervention agents (sometimes police) and mental health staff to convince the detainee of the benefit of staying overnight on a voluntary basis.

Re-entry

Forgiving and reintegrating wrongdoers, especially remorseful ones, are valuable both symbolically and practically. The left and the right ought to be able to unite behind a combination of restorative punishment followed by forgiveness as exemplified by re-entry programs both public and private. We dream of a future that connects our incarcerated population with services aimed at returning as many people back to their communities as possible, and that provides the tools to reduce their risk of recidivism. The process of re-entry from the justice system begins at intake, and the brick and mortar facilities housing inmates need to accommodate this process.

Restorative Justice

Seven empirical studies found restorative justice performed better than traditional criminal justice on all dimensions studied: victims and wrongdoers were more likely to think that the system, their judges or mediators, and the outcomes were fair. Legalese, procedural technicalities, and unfettered back-room deals should give way to more transparent and participatory procedures (Bibas, 2012).

Larger Roles in 2030

Defendants, victims, and communities can play larger roles through grand juries, consultation with prosecutors, rights to be heard in court, restorative justice conferences, and the requirement of defendants to work to support their families and victims.

Objective-based jail classification is used to determine housing assignment. The deflection of mental health and chemical addicted population means the jail can be smaller than ever. Disciplinary problems, violence, suicides, and staff absenteeism have declined year after year because of smarter staff, kinder buildings, and smaller populations.

In 2030, law enforcement personnel are trained to recognize the symptomatic behavior of the mentally ill and to assist in deflecting these individuals to stabilization centers staffed by mental health professionals rather than transporting them to jail intake. If an individual is arrested and taken into custody, the jail intake area has an open-seating area with views to the outside. This area is large enough to hold those eligible for bail, bond, or release on recognizance, so that they never need to spend a night in a cell.

The jail of the future also has courtrooms for initial appearances, hearings, and bench trials. If someone is released, they are free to exit from the front door of the jail into the free world without spending the night in jail. The Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee, (comprised of representatives from mental health, human services, police, courts, detention, prosecutor, local service providers and others) meets monthly to expedite court cases, reduce admissions, shorten length of stay in jail, implement standardized intake process, expand alternatives to secure detention, and promote more timely transfer to state facilities.

Conclusion

In the year 2030, jails are fewer in number than in the past, and communities are proud to have a detention center because it is viewed as one facet of restorative justice. Located in the very communities they serve, jails are seen as good neighbors. They are designed to be handsome civic buildings, sometimes located in plazas or with gardens. The structures that house the justice system are sited, constructed, and operated to minimize resource consumption. Ultimately, these detention centers create a netpositive impact on the community and the environment.

Recognizing that the vast majority of offenders return to the community, the jail of the future focuses on successful reentry to support the sustainability of people—by helping them to live better lives in which they are more loving, more productive, and more responsible.

References

AIA Academy of Architecture for Justice. (2010). Sustainable justice 2030: Green guide to justice. Retrieved from here.

Bibas, S. (2012). The machinery of criminal justice. New York: Oxford University Press.