Transformative Growth: The Impact of CGL’s Operations and Management Consulting

As part of our “50 Years Strong” series celebrating CGL Companies’ 50th anniversary, we’re exploring the rich history and growth of our various service lines. In our first three installments, we learned about the impressive journey of CGL’s Planning and Design services; how CGL redefined facility maintenance and management in justice ;and the ways in which CGL revolutionized owner representation in justice.

In today’s post, CGL’s Director of Justice Services, Karl Becker, sits down with Senior Vice President and operations and management consulting expert Kenneth McGinnis to reflect on the history of CGL’s operations and management consulting service line and its immense impact on helping to create a safer, more effective justice community.

An Enlightening Conversation with Ken McGinnis on CGL’s Legacy in Operations and Management Consulting

I had the honor of sitting down with Ken McGinnis, Senior Vice President at CGL, a distinguished leader in the field of corrections, and a longtime colleague and friend. Ken’s extensive career spans decades of transformative change in the justice community, and his insights have been instrumental in shaping the evolution and growth of CGL’s operations and management consulting services. Read on as we delve into his accidental entry into corrections, the significant shifts in justice practices over the years, and the challenges and innovations that lie ahead.

Ken, how in the world did you get into corrections, and where did your career begin?

Ken: Like most people, I didn’t plan to go into corrections at all. I was a graduate student at Southern Illinois University in their Center for Crime, Delinquency, and Corrections—a research-oriented master’s degree program.

A couple of things happened while I was there. One of my advisors was Myrl E. Alexander, who was Director of the Bureau of Prisons from 1964 to 1970. He was always encouraging us to visit the Marion Federal Prison, trying to convince us to get into the corrections business.

Then I was a research assistant for a professor who had a large federal research project on corrections and prisons. I ended up going to the Menard Correctional Center a couple of times a week to collect data, interview inmates, and interview inmate families for research. After about a year, they offered me a job. I had completed all my coursework and was just working on my thesis, so I figured, “Well, this is a good segue. I can get paid while I’m working on my thesis.” So I took a job at Menard in 1971.

That was my first job, and every time I got ready to leave, I got promoted, so I ended up staying. It was kind of an accidental career, to tell you the truth.

Ken McGinnis early in his career. McGinnis began his justice career by working at Menard Correctional Center in 1971.

You started on the program side, not the security side, correct?

Ken: That’s correct. The newly appointed Director of the Illinois Department of Corrections wanted to emphasize programming and specifically directed the institutions to hire degreed people with experience or training in rehabilitation programs. I fit the bill, so I was hired. It was a major conflict at the time because we were the first ones to come in and really do programming other than education programs. I started on the clinical side originally and was the Deputy Director of Programs for a while at Menard, so my early career was all on the program side.

For those unfamiliar with Menard, how would you describe it at that time?

Ken: Its history dates back to the Civil War. It was a very old, maximum-security prison with a capacity of around 2,600. It was an old-school prison when I went in there—a very violent place with a lot of racial and gang tension. The large population couldn’t be managed effectively due to limited housing options.

There were only two distinct housing units at the time, so you couldn’t separate or classify people effectively. It was difficult to manage. Even the program staff got involved with daily security and operations issues because of the facility’s complexity.

The potential for violence was everywhere, and it was a daily event. In the early ’70s, you had the emergence of Chicago street gangs moving into the prisons. The violence was constant—primarily inmate-on-inmate, but unfortunately, staff were sometimes harmed. It was a difficult time in the Illinois Department of Corrections, particularly at the three largest maximum-security facilities.

Eventually, I became Assistant Warden of Programs at Menard —way too young and way too early in my career. It was an absolutely great learning experience, though, because of everything that was going on. There were very extensive academic programs because Illinois had its own school district with a strong emphasis on education. There was a robust industry program, but beyond that, not much else. You could be pretty creative and innovative in getting things done.

This was a period of significant changes in prison management… were these changes driven internally or from external pressures like the courts or societal demands?

Ken: It was a combination of things. There wasn’t much public interest in prison systems back then; they operated independently. But we saw the emergence of the courts getting involved in constitutional issues, and Menard was involved in lengthy litigation over its conditions. That was truly an impetus for change. Court intervention forced the legislature to increase funding in areas like medical and mental health treatment.

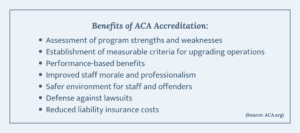

At the same time, the emergence of the American Correctional Association (ACA) standards played a significant role. Back then, in Illinois there was very little in terms of statewide policies and procedures—the system operated on local controls. The director adopted ACA accreditation as a goal, and the Menard administration aggressively pursued it. This allowed us to develop comprehensive policies and procedures for the first time, setting standards and holding people accountable. Accreditation was a major impetus for improving the system in the mid to late ’70s.

You have been active in the accreditation movement since its inception. Can you tell us more about the accreditation standards and how they were developed?

Ken: The ACA developed a Commission on Accreditation, which, after soliciting input from the field, created specific standards focusing on programming, staffing, facilities, and policies and procedures—with a strong emphasis on the latter.

Menard was one of the first to go through the accreditation process, which became controversial due to its conditions. Menard was actually the impetus for developing mandatory standards within the Commission. Prior to that, there were no mandatory standards. Before these mandatory standards, Menard met the accreditation process, which made many people scratch their heads. But it really was an impetus for dramatically improving the facility.

Menard had a major lawsuit regarding inmate health care delivery, leading to private contractors providing care and setting standards. Can you describe that process?

Ken: The litigation focused on health care, setting specific standards for physician hours on-site, the number of nurses, and overall health care staff. It was very difficult to recruit back then.

This was the early stage of private health care systems in corrections. We were short on health care hours and found a firm out of St. Louis that staffed industrial clinics and hospital emergency rooms. We signed a contract for physician hours with them, which eventually evolved into Correctional Medical Services and became one of the major private health care providers in the U.S.

There’s a consistent theme in correctional management between punitive approaches and rehabilitation. How have you seen this tension evolve over time?

Ken: It all goes in cycles. For example, recently there’s been debate and approval of reinstating Pell Grants for inmates to get college credits. In the ’70s and ’80s, Pell Grants were used extensively in prisons to provide programming and reduce idleness. Menard had several hundred inmates enrolled in college under Pell Grants. Then, in the mid-’80s, it was abolished due to budget cuts and controversy over using Pell Grants for convicted felons.

Now, 30–40 years later, it’s been reinstated. I’m not sure it’ll reach the peak numbers of the past, but times have changed.

Similarly, in the ’70s and ’80s, there was a tremendous emphasis on release preparation—then called “reintegration,” now “reentry.” There were extensive reintegration programs, including furloughs and community corrections. Some people may remember the Willie Horton case from the 1988 presidential election, where the reintegration programs involving furloughing inmates from prison became very controversial. Well, Illinois used that extensively at the same time.

Most states did. They had very extensive furlough programs and very extensive community corrections programs where people were early released from prison into halfway houses and community centers. In the case of Illinois, they were put on electronic monitoring. At one time, I recall that Illinois had, ~3,200 inmates early released from prison on electronic monitoring.

Willie Horton was a guy in Massachusetts who was in for first-degree murder but was eligible under the criteria because he was within six months of his earliest possible release date. He got furloughed, went to Maryland, and committed another murder. George Bush’s campaign raised that as an election issue in the 1988 election, and I think that became the tipping point for moving into truth in sentencing, abolishing early release programs, putting extensive limitations on early release and use of community correction centers.

Now we’re cycling back with reentry programs, though not necessarily for first-degree murderers. These things go in cycles, depending on mainly the political environment out there to accept these kinds of programs.

While working at IL DOC, you even had experience taking serious offenders into the community for events as a privilege and to expose them to the outside world, correct?

Ken: Yes, that was done extensively, tied to the earliest possible release date. In those days, with indeterminate sentencing in Illinois, if you were within eight months of your next parole date, you were eligible. Inmates participated in a wide range of community programs daily. The criticism of Massachusetts during the Willie Horton case was somewhat unfair but reflected national efforts to improve release mechanisms for all levels of offenders, not just minimum-security ones.

Large dorms commonly used in correctional facilities in the ’90s aren’t suitable for today’s inmate population. CGL has worked with many facilities over the years to address these issues and update their housing configurations to accommodate current populations. Pictured: The facilities in Ohio Correctional System originally featured large dormitory housing units, which CGL recommended sub dividing into smaller living clusters as part of its work on the Ohio Correctional System Master Plan.

How has the composition of the inmate population changed over time?

Ken: Many factors contributed to changes. Due to overcrowding and truth-in-sentencing emphasizing longer sentences in the ’90s and beyond, there was a push to find alternative programming. This exploded community corrections and alternative programs.

Low-level, nonviolent offenders were flushed out of the prison population. Today’s maximum-security prisons house more violent, long-term, repetitive offenders who are difficult to manage and present greater security risks.

In most states, extensive farm programs staffed by inmates have been scaled back or eliminated, with the land leased to local farmers. Industry programs are also difficult to staff due to restrictions. The targeted population has changed, affecting the needs of physical plants. Facilities built in the ’80s and ’90s are outdated and don’t match the current risk levels. Large dorms used extensively in the ’90s aren’t suitable for today’s inmate population. Many facilities built to address overcrowding during that time weren’t meant to be long-term. They’re reaching the end of their utility unless significant renovations occur.

For example, Illinois’ first new prison in decades was the Graham Correctional Center which was opened in 1980. After that, a majority of Illinois’ major construction projects were either renovations of mental health facilities with short shelf lives or temporary facilities designed for 15-year use. These have exceeded their intended lifespan.

I think as you go across the country, you see the same thing everywhere—because of the need to bring beds online very quickly, construction standards were reduced. And with the projected facility life no more than 20 years on average —those have far exceeded their shelf life.

Now most systems are faced with a decision on what to do with those facilities, how to replace them, whether to renovate and upgrade or just tear them down and build new. I think that’s going to be one of the major focuses of emphasis over the next decade is how to rehab all these facilities whose shelf life has really run out.

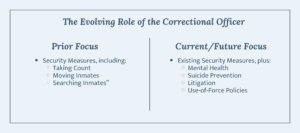

How has the role of the correctional officer evolved?

Ken: It’s always been a difficult job. Thirty years ago, the emphasis was strictly on security—counting, moving, and searching inmates. Today, officers must be aware of mental health issues, suicide prevention, litigation, and use-of-force policies. It’s a complex job, and we’re seeing dire staff shortages nationwide. Working conditions have worsened with overtime and double shifts.

We’ll need to revisit the system, refocus on training, and improve working conditions to attract sufficient staff. Interest in the corrections profession has changed significantly.

Describe your transition from a career in government to becoming a consultant. How did your experience inform your consulting work?

Ken: I was fortunate to have a good career. When I left Michigan, I joined Mike Fair, former Director in Massachusetts, in consulting. It wasn’t much different from my previous role—we reviewed programs and operations as independent third parties.

There was a lot of interest in using consultants, especially with increased litigation. We worked across the country, bringing best practices to various systems.

CGL’s Operations and Management Consulting team is able to provide such valuable insight and solutions to clients thanks to their direct experience as former administrators and directors of justice systems. Pictured above: Ken McGinnis alongside fellow former MDOC directors.

While visiting different systems, one of the themes that I often hear you tell administrators is that they’re “stepping over the bodies,” unaware of better practices due to being locked into old ways.

Ken: That’s accurate. As consultants, we gathered information to share with systems. From my days as a warden, I know you can get so involved in day-to-day survival that you miss obvious problems. It’s not anyone’s fault—it’s the nature of the business. Bringing in a third party can provide a helpful second look.

Organizations like the Correctional Leaders Association (CLA) and the ACA have improved information sharing between jurisdictions, making best practices more accessible.

Despite serious challenges, some things have improved. What progress have you seen over time?

Ken: The most obvious is physical plants, thanks to the building boom in the ’90s. Facilities are much better, allowing for effective separation and classification of inmates, improving security.

Data-driven classification systems, like those developed by Jim Austin at JFA, have improved facility safety. Training programs for staff have significantly improved. When I started, training was minimal—now it’s sophisticated, enhancing the quality of employees.

The emphasis on data analysis and best programs has improved facilities nationwide.

What do you think the next trends will be in improving state correctional systems?

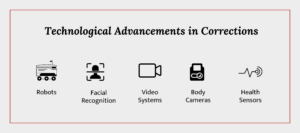

Ken: Technology will continue to grow, bringing valuable assets like video systems and body cameras. While helpful, they also make the job more challenging as officers are held accountable for every move.

Our colleague Steve Carter talks about robotics. With staff shortages, robotics and technology will likely play a larger role in monitoring inmate behavior and performance. We’re already seeing remote monitoring in healthcare.

There’s also a need to rebuild physical plants. States like Alabama and Arkansas are upgrading facilities to improve safety, working conditions, and staffing efficiency. We need to adjust to a new staffing reality and figure out how to staff facilities differently and more efficiently.

Technology also creates new challenges, like drones introducing contraband. Who would have thought that would be an issue five or ten years ago?

Technology also creates new challenges, like drones introducing contraband. Who would have thought that would be an issue five or ten years ago?

Ken: Exactly. Same with cell phones. Twenty years ago, we didn’t have cell phones; now they’re everywhere. The CLA and leaders like Director Sterling in South Carolina are working to control these issues. Drones and cell phones are serious security challenges for high-security facilities.

Despite changes over your career, what constants remain in correctional work?

Ken: It’s always been a complex and dangerous business. For line officers, it’s a very dangerous yet rewarding profession—you won’t be bored working in corrections. The constant emphasis on basic operational policy, procedure, and execution hasn’t changed. These are the ABCs of corrections, and they must be done properly and consistently, even as technology aids these efforts.

Looking back, can you point to projects that significantly improved conditions for staff and inmates?

Ken: In 1982, as warden of the new facility in Hillsboro—the first new prison in Illinois—I think that was a tipping point. We implemented different design standards and a new environment for inmates. It was successful, but benefits were negated by growth due to truth-in-sentencing laws.

More recently, Alabama’s efforts are very creative and innovative. As Commissioner Dunn has said, it could be a generational change for Alabama by replacing the entire system with new complexes. They have one under construction and a second one planned. This model could be adopted by other states to replace outdated and inefficient facilities with ones designed to meet today’s demands.

The project is a game-changer and Alabama should be proud of their efforts despite costs and delays. We’re proud at CGL to be participants in that. It’s a concept other states are starting to consider and will eventually implement.

The Expertise and Experience to Move Systems Forward

From his accidental career start to leading major corrections departments and becoming a key figure in consulting, Ken’s journey reflects the dynamic nature of the corrections field. The challenges of the past—from managing violent prisons with limited resources to navigating cycles between punitive and rehabilitative approaches—highlight the resilience and adaptability required in this profession.

Innovation – whether through improved facilities, advanced technology, or data-driven classification systems – underscores the ongoing need for progress in corrections. Ken’s reflections on constants—the complexity and inherent dangers of the job and the unwavering need for solid policies and procedures—remind us of the foundational elements guiding the justice community.

Ken’s unique experience of having been in the clients’ shoes—facing the same struggles and issues that correctional leaders grapple with today—brings invaluable perspective to CGL’s operations and management consulting team. Having a deep understanding of the inner workings of state systems allows him and our team to provide pivotal insights and develop impactful strategies that have immediate and long-term beneficial impacts on justice facilities and systems. It’s this hands-on experience that enables us to truly move the needle in effecting meaningful change.

If you’ve enjoyed this installment of our “50 Years Strong” series, we invite you to visit CGL’s 50th Anniversary landing page to catch up on previous posts and learn more about the evolution of our service lines over the past 50 years. Together, we’re looking forward to the next 50 years of making a difference in the justice community.